Martial Bourdin: Anarchist hoist with his own petard

by Bob Davenport

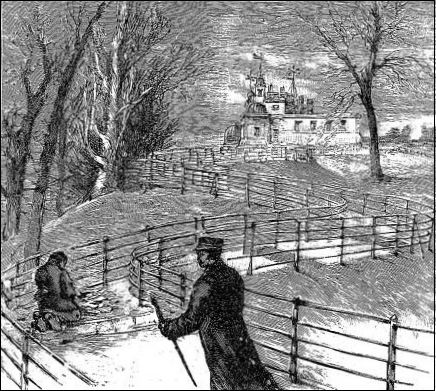

On Thursday 15 February 1894 some schoolboys were walking through Greenwich Park when, at about 4.50 p.m., they heard an explosion and saw a column of smoke. They ran towards its source on the zigzag path that rises through the park, and saw a kneeling man about 70 yards from the Royal Observatory. Looking for help, they met park-keepers heading to the scene. They found the man covered in blood and with a handkerchief wrapped round his hand. ‘Fetch a cab,’ he told them, and he asked to be taken home. He was in fact taken to the nearby Seamen’s Hospital, where he died at 5.40 p.m. He had been carrying a bomb, which had exploded and blown away most of his left hand and severely injured his abdomen and chest.

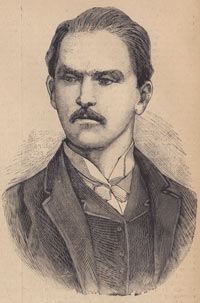

The dead man was Martial Bourdin, a 26-year-old Frenchman, one of eight children in a working-class family from Tours. A tailor by trade, he seems at one time to have been a member of a group of about 60 anarchist tailors in Paris called L’Aiguille – The Needle. After a short prison sentence for trying to organise a public meeting, in about 1887 he moved to London, where his brother Henri had a women’s-tailoring workshop at 18 Great Titchfield Street and gave him occasional piecework.

Bourdin became a regular at the Autonomie Club, eventually at 6 Windmill Street, off Tottenham Court Road, in an area which, said the Manchester Guardian after the explosion, was ‘notorious as the favourite haunt of the most advanced section of the Socialist party and of the Anarchists, English and foreign’. The club itself had ‘been known to the police for years past as the resort of political desperadoes of all nationalities; but … [had] never been interfered with, mainly because it furnished a convenient means of keeping the Anarchists under surveillance’. Bourdin helped in fund-raising for destitute anarchists in flight from the Continent, acted as secretary of the French-speaking section of the club for a time, and took part in demonstrations in Trafalgar Square.

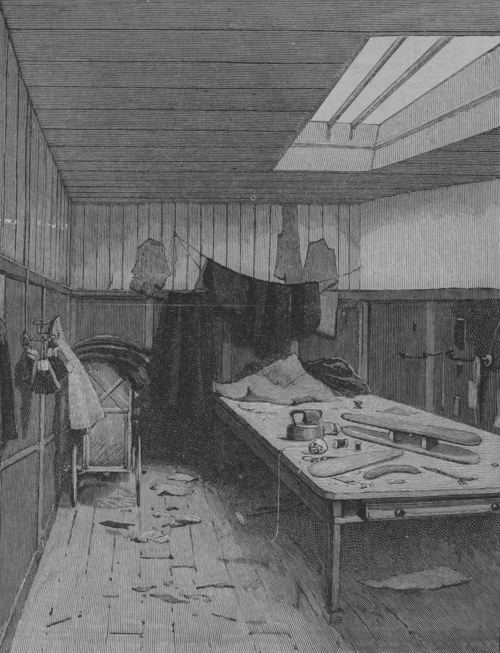

After a period back in France he returned to London and then went to the USA, spending time in New York and Chicago, before returning to lodgings at 30 Fitzroy Street in late 1893.

At noon on the day of his death he had visited his brother to ask for work but had been told there was none, had lunched with two other men off Fitzroy Square, then – alone – at 3.10 p.m. had taken a tram from Westminster Bridge to East Greenwich, where he arrived at 4.19, having apparently overshot his stop, for he asked for directions back to Greenwich Park. On entering the park he was observed to have a package about the size of a brick in his left hand. This was the bomb which later exploded.

Colonel Vivian Majendie, HM Chief Inspector of Explosives, told the subsequent inquest that he believed that the explosion had occurred about 46 yards from the Royal Observatory, and Bourdin had then staggered some way back down the path. The results of the explosion were not consistent with Bourdin having tripped, and Majendie thought the bomb must have been mishandled in some way. He believed Bourdin had been intending to blow up the observatory – and The Times speculated that there might have been an element of French jealousy of the observatory’s worldwide pre-eminence involved in this. But anarchists declared that they would never attack an institution dedicated to the advancement of humanity, and Bourdin’s intentions remain unclear.

He had had just under £13 in his pockets when he was killed – equivalent to about £1,500 today – as well as instructions for bomb-making copied from a book in the British Museum. An obituary in the socialist/anarchist paper The Commonweal claimed that Bourdin had been en route to a deserted location to try out the bomb; others claimed that he intended to pass the bomb on to another anarchist somewhere by the Thames, for transmission to France, where an anarchist bomb had caused death and injury in a Paris café three days earlier, or that he was going to take it to France himself and had gone to Greenwich to try to lose any police spies who might be following him.

The jury at the inquest found that Bourdin’s death had been caused by shock and haemorrhage resulting from the violence of explosives of which he was in unlawful possession. The coroner said this amounted to a verdict of felo de se: that Bourdin had been engaged in an unlawful act which had led to his own death.

Anticipating such a verdict, it had been asked in Parliament whether the authorities should themselves dispose of Bourdin’s body, to avoid his funeral being turned into an anarchist demonstration; instead the Home Secretary, Herbert Asquith, ordered that the police should prevent any procession behind the hearse and any speeches at the graveside.

The funeral took place on 23 February, and the Guardian thought it ‘showed humanity in its most loathsome aspect’. Bourdin’s body was by then in an undertaker’s in Chapel Street, off the Edgware Road, and a crowd began to assemble near there around noon. It contained a large number of detectives and some faces familiar from the Autonomie Club, said The Times, but ‘For the rest, the crowd consisted of the roughest of the rough, and its characteristic feature was a sullen silence as of men who had a purpose; but that purpose was not to demonstrate in favour of Anarchy.’

At one o’clock a glass-sided hearse and a single mourning coach drew up to the undertaker’s door and the police cordoned off the street about 50 yards on either side of it. Half an hour later, to roaring and hissing from the crowd, the coffin was carried into the hearse and Bourdin’s brother and three other men entered the other carriage. Two anarchist flags were raised, but were immediately torn to pieces.

The route to be taken had been kept secret even from the undertaker, though it had been expected to pass through Fitzroy Square, where some medical students created a disturbance and were arrested. Instead the carriages were directed towards Lisson Grove, and after some tumultuous scenes – The Times reckoned the hearse would have been wrecked and Bourdin’s body torn to pieces were it not for the police – the crowds died out around St John’s Wood and progress was swift up Abbey Road and on to St Pancras Cemetery.

The Guardian’s reporter decided to head off the cortège by dashing to King’s Cross and taking a train to Finchley. He found that

The train was crowded, and among the passengers were many Anarchists. When you suspect his presence it is generally easy to see who is an Anarchist and who is not. The negative evidence is valuable, for there are so many things that an Anarchist cannot be – for instance, he cannot be a clergyman, or a schoolmaster, or a sea captain, or a soldier, or an Irish estate agent, or a shopwalker, or a college don. I saw who were Anarchists plainly enough. Some few were Englishmen, with ragged beards and hair, and slimy black apparel. Three Frenchmen and a hollow-cheeked Frenchwoman also belonged to the poverty-stricken tribe of Anarchists. Then there was a group of five Frenchmen of quite a superior class, well dressed, and smoking cigarettes. They were talking eagerly and passionately, and had I cared about eavesdropping I might have heard all they said.

At about 3.15 a detachment of police cleared a space around the grave prepared in a unconsecrated part of the cemetery. A crowd of some 200–300 was then present, according to The Times – ‘with not many Anarchists or foreigners among it’ – but the numbers increased when the hearse appeared and some of those who had been kept outside the cemetery succeeded in following it in. Then, ‘in less than a minute’, the coffin was taken out of the hearse, a wreath was placed on it, and it was lowered into the grave. A man named Quinn, who had been allowed to the graveside as one of the mourners, leaped forward and shouted out ‘Fellow Anarchists … ,’ but a policemen interrupted with ‘No speaking, please; no speeches here,’ and he was bundled away followed by a mob shouting ‘Hang him!’ A contingent of police, some of them mounted, escorted him safely to the cemetery gates and into the mourning coach, where Henri Bourdin and his friends almost immediately joined him and they drove off.

Ten minutes later the grave had been filled in and the police were dispersing the crowd, and in another half-hour all was quiet. ‘Such’, said The Times, was an Anarchist funeral.’

Bourdin’s grave is unmarked, but he has a memorial of sorts in fictional characters that have been based on him, or perceptions of him. He appears as Augustin Myers in the 1903 novel A Girl Among the Anarchists by ‘Isabel Meredith’ (a pseudonym for Helen and Olive Rossetti), which follows the theory, current after his death, that Bourdin had been set up by his brother-in-law, H. B. Samuels, who was supposedly a police spy. Better known is Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Agent (1907), where the slow-witted but idealistic Stevie is blown up after having been induced to plant a bomb outside the Royal Observatory by his agent-provacateur brother-in-law, Adolf Verloc; this again reflects beliefs – now discredited – held about Bourdin and H. B. Samuels at the time. Alfred Hitchcock followed this line in his 1936 film Sabotage. And, in real life, in July 1996 the FBI described how the ‘Unabomber’, Theodore Kaczynski, had apparently often used the alias ‘Conrad’ during his 18-year bombing campaign against scientific institutions.

SOURCES

• Paul Gibbard, ‘Bourdin, Martial (1867/8–1894)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004, January 2008

• Manchester Guardian, 16 February 1894 (‘The Foreign Anarchists in London’), 20 February 1894 (‘The Anarchist Plots in London’), 24 February 1894 (‘The Anarchists in London: A Scene at Bourdin’s Interment’), 27 February 1894 (‘The Bomb Explosion in Greenwich Park’)

• Propaganda by Deed: The Greenwich Observatory Bomb of 1894

• The Times, 20 February 1894 (‘The Greenwich Explosion’), 21 February 1894 (‘Parliament: House of Commons: The Anarchist Bourdin’), 24 February 1894 (‘The Anarchist Funeral’), 27 February 1894 (‘The Anarchists’ and ‘Inquest on Bourdin’)

This is fascinating. I’ve just finished reading Rachel Holmes’s biography of Eleanor Marx but strangely it doesn’t seem to mention the Greenwich Park explosion or Bourdin. His funeral sounds grim.

LikeLike

Thanks. Judging by the coverage in the Times and Guardian’s online archives – more than I’ve referenced – and the sources listed in his ODNB entry, Bourdin received a lot of press attention at the time. I’m a bit puzzled that it should be nine years later that a version of him first appeared in fiction.

LikeLike

[…] terrorisme en de negatieve associatie Het verhaal van Martial Bourdin Theodore Kaczynski: ‘De […]

LikeLike