Michael and Bessie Gunn: Theatre people

by Bob Davenport

As mentioned in an earlier post, when the actress Olga Brandon died in May 1906 and was buried in a common grave in St Pancras Cemetery, a friend of the writer George R. Sims was instrumental in having her moved to a private plot. On reflecting on this in his memoirs, Sims noted that ‘now the dead actress rests in a grave near that of Michael Gunn.’

Michael Gunn (1840–1901)

Michael Ralph Gunn was born in Dublin in 1840, the second of eight children of Michael and Ellen Gunn, and was baptised on 31 May that year. His mother was a corset-maker, and his father was originally a piano tuner, before founding a company – M. Gunn & Sons – that sold pianos and sheet music.

Michael was helping his father in the business and also keeping its books by the time that, in April 1861, Michael senior was killed in a bizarre accident. He was one of the six passengers inside a Dublin omnibus which, having started its journey at about 9 o’clock at night, stopped at the Portobello canal bridge, to which there was a sharp ascent on both sides.

The driver pulled up to let out a passenger on the bridge. While the conductor was taking the fare the omnibus began to back down the incline towards Rathmines. In the effort to get on the horses, which were fresh and spirited, one or both became restiff, the pole got entangled in the harness, the driver lost control over them, the omnibus continued to back up on the road towards Portobello Barracks, and then, turning rather sharply round, it was pushed violently up the rising ground to the lock basin, bursting and passing through the wooden railing; and before any assistance could be rendered the omnibus, horses, and all were precipitated into the canal.

They had fallen into a lock chamber, and a witness told the subsequent inquest that, as efforts were made to rescue them,

To my great surprise I saw a great rush of water into the chamber. I went to the upper gate and met O’Neill, the lockkeeper, who had the key of the sluice-gate in his hand. I bawled out to him, ‘In the name of God, O’Neill, what have you done?’ ‘I’ll float the ’bus,’was his answer… He seemed unable to distinguish between a ’bus and a boat. It is a fact that the water rose rapidly and covered the omnibus.

In its verdict, the inquest jury declared that ‘We do not attach any blame to any of the persons concerned, believing that all exerted themselves to the best of their judgement on that occasion’; nevertheless, 50 years later ’Jimmy’ Glover, the master of music at the Drury Lane Theatre, who was born in Dublin in 1861, recalled the folk memory of the accident in these terms: ‘“Begorra!” shouted the bewildered lock-keeper, “I’ll save their lives by floating the ’bus,” which he immediately proceeded to do by opening the sluices, filling the lock and drowning all the passengers.’

The fatal omnibus accident at Portobello, as envisaged by the Illustrated London News

In the following years Thom’s directory of Dublin listed Michael junior as a ‘professor’ (i.e. teacher) of singing, with his older brother, John, as a cello teacher and his younger brother James as a piano tuner. Michael was also a talented violinist and pianist, and in 1865 directed some of the music played at the reopening of St Teresa’s church in Dublin. He served on the municipal council in the late 1860s and into the 1870s, until the need to travel for his developing business activities made it impossible to continue.

He was a keen traveller and spoke French and Italian fluently, as well as some German, and it is said that ‘his experiences in France and Italy, with the various suggestions that from time to time reached the Corporation, suggested to him the building of a theatre in Dublin.’

In April 1871 he and his brother John received permission from the Letters Patent Office to establish ‘a well regulated theatre and therein at all times publicly to act, represent or perform any interlude, tragedy, comedy, prelude, opera, burlette, play, farce or pantomime’. The theatre, to be named the Gaiety, was designed by C. J. Phipps, who had already been responsible for three London theatres as well as the rebuilt Theatre Royal in Bath, and it was built in South King Street, Dublin, in just 28 weeks, at a cost of £26,000. It opened on 27 November 1871, when the actress Mrs Scott Siddons prefaced a performance of She Stoops to Conquer with

Scarce hath the earth her journey half way run,

In changing seasons round the central sun,

Since Art, obedient to the Muses’ call,

Laid the foundation of this Thespian Hall.

Then day by day, in fair proportions grew,

The beauteous fabric that now meets the view.

The graceful shafts with floral sculpture crowned,

Supporting tier on tier that rises round,

With many a rich device by genius planned,

Wrought by the painter’s brush, the carver’s hand.

’Till amid gleaming gold and flooding light –

Resplendent shines ‘The Gaiety’ tonight.

The auditorium of the Gaiety Theatre (as redecorated by Frank Matcham in 1883), from the souvenir booklet produced for the theatre’s twenty-fifth anniversary

The new theatre was not without competition: the Theatre Royal (originally the Albany New Theatre) had been in Hawkins Street since 1821, and there was also the Queen’s in Pearse Street. However, the Gaiety differed from these in not having its own company but instead acting as a receiving house for visiting English companies with first-class productions of drama, musical comedy and opera. Thus the performance of She Stoops to Conquer (which was followed by the burlesque La Belle Sauvage) on the first night was given by the St James’s Theatre Company of Mrs John Wood. And the enduring tradition of the Gaiety pantomime began in December 1873 with Edwin Hamilton’s Turko the Terrible.

Earlier that year M. Gunn & Sons had been wound up, ‘a change having taken place in their Partnership Arrangements in consequence of the retirement of Mrs. Gunn, Senr.’, but in March 1874 the Gunn brothers expanded their activities by taking on the Theatre Royal, which was thereafter managed by Michael while John ran the Gaiety.

In September 1875 the Gaiety Theatre was one of the venues visited by a company whose programme included the first tour of a Gilbert and Sullivan opera – Trial by Jury – organised by Richard D’Oyly Carte. Michael Gunn took an interest in Carte’s ambition to set up a permanent home for light opera in London, and eventually became his business manager. It was he who sent out two touring companies of HMS Pinafore in the UK while Carte was in the USA to counter unauthorised productions there, and he was involved in Carte’s battles with the Comedy Opera Company in London when it tried to continue with Pinafore when its agreement with Carte expired. He also played a large part in realising Carte’s plans for a theatre of his own, the Savoy: besides investing in it himself, he helped Carte find other investors, and negotiated additional loans for the building. In a letter to his solicitor, Carte – who became a close friend as well as a business associate – later said of Gunn, ‘I have a greater respect and regard for him than I think for any man living except my father.’

The Savoy – claimed as the first public building to be lit by electric light – opened on 10 October 1881, and when, in the new year, Carte was again in America, Gunn took over its management, as well as supervising the G&S touring companies, which he continued to do until 1884. Thereafter he continued his association with Carte as a major shareholder and a director of the Savoy Hotel, which opened in 1889.

Bessie Sudlow (1849–1928)

It was not only Carte’s plans for light opera in English that interested Gunn during the performances of Trial by Jury in Dublin in September 1875: it was supposedly then that he also took an interest in a member of the opera’s cast – Bessie Sudlow, who sang the part of the Plaintiff.

Sudlow had been born Barbara Elizabeth Johnstone (or, in some records, Johnston) in Liverpool on 22 July 1849, the daughter of George Johnstone, a captain in the merchant navy, and his Irish-born wife, Eliza, née Lee, who had been widowed by the time of the 1851 census. By 1870 Eliza had married Thomas Sudlow, from Liverpool, and she and Barbara were living with him and four other children in America. Barbara, using the name Bessie Sudlow, had already embarked on a career on the stage. In October 1868, commenting on the end of the run of the spectacle Undine at the Academy of Music, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle wrote:

The lady who sustained the role of Undine, and whose singing has been especially noticed as the musical feature of performances, has shared the fate of Byron’s hero, of having her name spelled wrong in bills and newspapers. Her name is Miss Bessie Sudlow. She is a resident of Brooklyn, and has obtained some local celebrity by her musical talents. She gives promise of future eminence on the stage. She has all the advantages of youth, comeliness, a good voice well cultivated, and a graceful ease of manner.

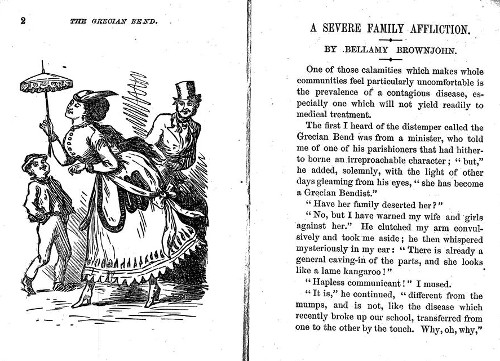

A month later she appeared in The Lancashire Lass at the New Chesnut Street Theatre in Philadelphia and ‘acted well her part, but the “Grecian bend” which she affected was in shocking bad taste, and certainly out of date … The ridiculous postures of Miss Sudlow were received with such derisive laughter that it is to be hoped that this lady will conform her dress to the times.’ (A week later it was reported that the Grecian bend had been abandoned.)

The Grecian bend (‘an affected carriage of the body, in which it is bent forward from the hips’ – Oxford English Dictionary) illustrated and deplored, from The Grecian Bend: What It Is (1868)

In January 1869 she appeared in the opening production of the new Tammany Theatre in New York: the burlesque The Page’s Revel, or the Summer Night’s Bivouac, an ‘exceedingly stupid extravaganza … in which some dozen or so … young ladies looked remarkably pretty’. Burlesques – usually parodies of well-known works, often risqué in style and featuring music and dance, with many of the male roles being played by actresses as breeches roles, to show off their physical charms – were to be a mainstay of Bessie’s early career, both in New York and on tour, including spells with Lydia Thompson’s celebrated ‘British Blondes’ troupe and with the Lisa Weber Burlesque Opera Troupe – ‘the raciest, jolliest little company of people in the country’, according to the Auburn Daily Bulletin. Productions in which she appeared included The Burlesque of Robinson Crusoe, The Forty Thieves, Sinbad the Sailor, Ixion (in which she ‘looked very well as Venus’), Bad Dickey (a spoof of Richard III, in which, as Catesby, she ‘had little else to do but look well, in which she was successful’) and Don Carlos (based on ‘one of Verdi’s last, feeblest and most worthless productions’ and in which she was ‘altogether a great attractive force to the company’).

She also appeared as a singer in mixed variety bills alongside the likes of Americus the child violinist and G. W. Jester, the Man with the Talking Hand. She was well received: in Baltimore, the New York Clipper reported in October 1870, ‘Miss Bessie Sudlow, serio-comic vocalist, has won golden opinions. Her rendition of “Sweet Spirit Hear My Prayer” and “By Killarney’s Lakes and Vales” is truly excellent.’ And as Mollie Malone in The Green Banner, or the Heart of Ireland at the Globe Theatre on Broadway in February 1871 she had ‘a new song, written and dedicated to Ireland’s exiled patriots’.

She became particularly associated with the Niblo’s Garden theatre on Broadway, where she was the Player Queen in Hamlet and later played Osric in Hamlet and Phoebe in As You Like It as part of a ‘Grand Shakespearian Combination’ starring Mrs Scott Siddons as Ophelia and Rosalind. In June 1871, announcing her booking for the Niblo’s summer season, the Brooklyn Daily Union commented that, ‘although her connection with the stage has not been more than two or three years, she has, by her talent, taken a high position in histrionic art, having appeared with marked success at Havana, New Orleans, St Louis, and most of the large cities in the States.’ And when, in December that year, she was one of the cast of some 200 in a revival of the ‘intricate and incomprehensible drama’ The Black Crook – a mishmash of Goethe’s Faust, Weber’s Der Freischütz, and other well-known work, and often considered to be the first piece of musical theatre that conforms to the modern notion of a ‘book musical’ – the Brooklyn Daily Eagle noted that

Miss Bessie Sudlow … has mounted continually higher on the professional ladder ever since she first went on the stage. Five years ago Miss Sudlow was a Brooklyn school girl, her parents still residing in this city. She had a very sweet voice, and for some time sang in the choir of St. Mary’s Church … She has been steadily improving until she can now vie with any actress on the Metropolitan boards.

During 1872–3 she took the title role in Jenny Lind (‘Jenny Leatherlungs’), which toured with Ned Buntline’s play The Scouts of the Prairie, featuring ‘Buffalo Bill’ Cody and ‘twenty real Pawnee Indians’. She also appeared as the Indian maiden Dove Eye in the Buntline play, and it is said that during one performance Buffalo Bill propositioned her while on stage. She was so outraged that she hit him over the head with one of the war clubs lying about and, when he fell to the floor, she sat on him until she had composed herself sufficiently to leave the theatre.

Bessie Sudlow in an unknown role

After spells in revivals of The Black Crook and Undine and other work including ‘a spectacular extravaganza in three acts and a prologue’ called The Children in the Wood, in which she was ‘encored every evening for the song “The Harp in the Air”’, in September 1874 it was announced that she was joining Lydia Thompson’s company at the Charing Cross Theatre in London, opening in H. B. Farnie’s burlesque Blue Beard, which had already been performed 470 times in America and proved a great success both in London and on tour.

In January 1875 she was in the pantomime The Yellow Dwarf at the Theatre Royal, Dublin – ‘a very graceful and attractive actress and sings pleasingly’ was The Era’s verdict – and in March she was in The Isle of Bachelors (an English version of Charles Lecocq’s comic opera Les cents vierges) at the Gaiety. Then in June she volunteered her services for a promenade concert held at the Theatre Royal in honour of the American team taking part in an Irish–American International Rifle Match in Dublin. Her performance of ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ was so enthusiastically received that it took ten minutes for the applause to subside so that she could give an encore, and her success was reported in several papers in the USA. Although it is usually said that she met Michael Gunn when she returned to Dublin in Trial by Jury three months later, as mentioned above, it seems improbable that they would not have met during one of these earlier visits.

In October 1875 Bessie appeared in an English version of another Lecocq opera, Fleur de Thé, at the Criterion Theatre in London. As the actress and manager Emily Soldene recalled in her memoirs:

Miss Bessie Sudlow, as ‘Cæsarine,’ made an immediate success under peculiar and adverse circumstances. It seems the Lord Chamberlain at the last moment objected to the original cast, and said unless a certain character was cast differently the piece could not be played. Mr. D’Oyly Carte, in agony, wired Mr. Michael Gunn of Dublin. Mr. Michael Gunn sent on Miss Sudlow. She studied the part in twenty-four hours, played it in boots damp from Davis, in dresses that had to be pinned on her. She sang songs she did not know to tunes she had never heard, wedded to words improvised as she went along. But she was all right, ‘pulled through,’ as she says, by ‘that dear Goossens,’ the conductor. When the notices came out, Miss Bessie Sudlow found herself famous; she had captured the town.

She started 1876 back in Dublin, in Dick Whittington and His Cat at the Theatre Royal: ‘Her acting was as fresh as a daisy, and her sparkling vivacity and pleasant manner again won showers of applause and golden opinions,’ The Era reported. In the summer she was with Doyly’s Carte’s company in Manchester. Then on 26 October 1876 she and Michael Gunn were married in St Marylebone parish church, London – Bessie was given away by George Dolby, who had managed many reading tours for Charles Dickens, and Michael’s best man was Richard D’Oyly Carte – and in the following January the lord mayor of Dublin presented them with ‘an illuminated address and a valuable service of plate of solid silver’ on behalf of subscribers in honour of their marriage.

Thereafter Bessie appeared only occasionally on stage: in 1877 she again appeared as the Plaintiff in extracts from Trial by Jury at a benefit concert in the Theatre Royal; in 1878 she appeared there as Cinderella, then in an amateur charity performance of The Two Roses, as Lady Teazle in The School for Scandal, and as Ariel in The Tempest; in 1880 at the Gaiety she was Kate Hardcastle in performances of She Stoops to Conquer to mark the tenth anniversary of the theatre’s opening and Lady Teazle in some performances of The School for Scandal, and in 1887 she sang Azucena in extracts from Il Trovatore in a benefit concert there.

She and her husband eventually had six children. Three of them – Kevin, Haidee and Agnes (later Lady Webb) – had careers on the stage, and the fourth child, Selskar, had a distinguished international career in public health. Selskar was also a friend of James Joyce. In a letter to his friend C. P. Curran in July 1937, Joyce wrote:

Selskar Gunn (without an ‘e’) used to come with us to the opera … He is the son of Michael Gunn. The brother James was a good friend of my father’s … He [Selskar] told me his sister Haidée had drawn his attention to the many allusions to her father and mother (‘Bessie Sudlow’) in W.i.P. [Work in Progress, later published as Finnegans Wake].

Michael Gunn has been said to be a recurrent creator–father–god figure in Finnegans Wake, where he first appears as ‘Mr Makeall Gone’. He is also mentioned in a number of places in Joyce’s Ulysses – for example:

What had prevented him [Leopold Bloom] from completing a topical song (music by R. G. Johnston) on the events of the past, or fixtures for the actual, years, entitled If Brian Boru could but come back and see old Dublin now, commissioned by Michael Gunn, lessee of the Gaiety Theatre, 46, 47, 48, 49 South King street, and to be introduced into the sixth scene, the valley of diamonds, of the second edition (30 January 1893) of the grand annual Christmas pantomime Sinbad the Sailor (written by Greenleaf Whittier, scenery by George A. Jackson and Cecil Hicks, costumes by Mrs and Miss Whelan produced by R. Shelton 26 December 1892 under the personal supervision of Mrs Michael Gunn, ballets by Jessie Noir, harlequinade by Thomas Otto) and sung by Nelly Bouverist, principal girl?

Throughout his work with Carte, Gunn had remained involved in the Dublin theatre scene. Sir Charles Cameron, who for over 50 years was in charge of the public-health department of Dublin Corporation, recalled in 1913 that

The late Mr. Michael Gunn, one of the two brothers who founded the Gaiety Theatre, was much given to generous hospitality, in which he was assisted by Mrs. Gunn, one of the best hostesses I have ever been entertained by. There were few theatrical stars who visited Dublin who were not in their time entertained at dinner or supper by Mr. and Mrs. Gunn. To many of those entertainments I was invited, and in that way got to see the actors and actresses when they appeared as themselves and not as some other persons.

John Gunn died in 1878, and Michael was then responsible for both the Gaiety and the Theatre Royal. Artists who appeared at those theatres under his management included Sarah Bernhardt, Ellen Terry, Henry Irving and Beerbohm Tree, as well as many international opera stars.

In February 1880 the Theatre Royal caught fire shortly before a charity performance, and was burned to the ground with the death of the stage manager. While nothing was happening to its site, in the early 1880s Michael was involved in productions at the Olympic, Avenue and Lyceum theatres in London, as well as at the Gaiety, including an unsuccessful attempt to establish Edward Solomon and Henry Pottinger Stephens as a light-opera team to rival Gilbert and Sullivan. It was suggested in the American press – which continued to take an interest in her and often reported on her visits back to the States with her husband – that in 1883 Bessie was instrumental in getting her stepfather a job as the business manager of the Lyceum; he and her mother had divorced in 1877. Eventually, in November 1886, Michael opened a concert and meeting hall, the Leinster Hall, on the old Theatre Royal site, with Adelina Patti singing at the opening.

The Leinster Hall in 1887 (from The Graphic)

A concert at the Gaiety in November 1896 to mark the twenty-fifth anniversary of its opening also marked the end of Michael’s management of the theatre. He was in poor health – he was not even well enough to attend the concert – and he handed over the running of the Gaiety to his late brother John’s son, also named John. The Leinster Hall was sold to a consortium led by the actor-manager Frederick Mouillot, which revamped it and opened it as a new Theatre Royal at the end of 1897.

‘Mrs Michael Gunn’, from the souvenir booklet produced for the Gaiety Theatre’s twenty-fifth anniversary, in 1896

Michael and Bessie moved to London, though retaining links with Dublin – they were there at the time of the 1901 census, when Bessie’s mother was also part of their household. Michael died at his London home, St Selskar’s, Eton Avenue, Belsize Park, on 17 October 1901 from ‘a complication of diseases’, though it was stated that he ‘had been ill for some considerable time with diabetes’. He was buried in St Pancras Cemetery on 21 October, and left an estate in England of £17,489 (equivalent to about £1.9 million today).

Not long after that, John Gunn junior moved to Australia ‘to recoup his health’, and the Gaiety passed into the hands of the Associated Managers of the United Kingdom. Sometime afterwards, however, Bessie was appointed its manager, in which role she continued until May 1909, when it was taken over by the Theatre Royal Co. Ltd. She died in Hove, Sussex, on 27 January 1928, and was buried with Michael on the 30th.

Michael and Bessie Gunn’s grave in St Pancras Cemetery

SOURCES

• The Advocate (Melbourne), 14 December 1901 (‘Death of Mr. Michael Gunn’)

• Michael Ainger, Gilbert and Sullivan: A Dual Biography (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002)

• Auburn Daily Bulletin, 26 May 1870 (Lisa Weber Burlesque Opera Troupe, Don Carlos)

• British Newspaper Archive – various mentions of Gunn and Sudlow

• Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 9 October 1868 (Undine), 16 December 1871 (‘has mounted continually higher’)

• Brooklyn Daily Union, 8 June 1871 (‘a high position in histrionic art’)

• Sir Charles A. Cameron, Reminiscences (Dublin: Hodges, Figgis & Co.; London: Simpkin, Marshall & Co., 1913)

• Chronicling America website – various mentions of Gunn and Sudlow

• 1871–1971: One Hundred Years of Gaiety (Dublin: Gaiety Theatre / Eamonn Andrews Productions, 1971)

• The Era, 17 January 1875 (The Yellow Dwarf), 2 January 1876 (Dick Whittington and His Cat), 29 October 1876 (‘Marriage of Miss Bessie Sudlow’), 28 April 1878 (‘Death of Mr. John Gunn’), 23 October 1909 (John Gunn junior to Australia)

• Evening Express (New York), 5 January 1869 (The Page’s Revel)

• Evening Freeman (Dublin), 2 March 1865 (St Teresa’s church)

• Evening Telegraph (Philadelphia), 10 and 17 November 1868 (The Lancashire Lass)

• Evening Telegram (New York), 11 February 1871 (The Green Banner)

• Freeman’s Journal (Dublin), 27 February 1875 (The Isle of Bachelors)

• Kurt Gänzl, The Encyclopedia of the Musical Theatre (Oxford: Blackwell Reference, 1994)

• James M. Glover, Jimmy Glover – His Book (London: Methuen, 1911)

• The Graphic, 10 December 1887

• The Grecian Bend: What It Is (New York: Grecian Bend Publishing Co., 1868)

• ‘Gunn, M. (& Sons)’, Dublin Music Trade website

• James Harty III, James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake: A Casebook (Abingdon: Routledge, 2015)

• Illinois Digital Newspaper Collections – various mentions of Gunn and Sudlow

• Illustrated London News, 20 April 1861

• James Joyce, Selected Letters, ed. Richard Ellmann (London: Faber, 1975)

• R. M. Levey and J. O’Rorke, Annals of the Theatre Royal, Dublin, from its Opening in 1821 to its Destruction by Fire, February 1880 (Dublin: Joseph Dollard, 1880)

• National Police Gazette (New York), 29 December 1883 (Thomas Sudlow at the Lyceum)

• National Republican (Washington DC), 2 May 1873 (‘twenty real Pawnee Indians’)

• New York Clipper, 23 October 1869 (Ixion), 18 December 1869 (Bad Dickey), 15 October 1870 (‘golden opinions’), 20 December 1873 (The Children in the Wood), 10 February 1877 (‘an illuminated address’)

• New York Herald, 27 November 1870 (‘Grand Shakespearian Combination’)

• NYS Historic Newspapers website – various mentions of Gunn and Sudlow

• Robert O’Byrne, Dublin’s Gaiety Theatre: The Grand Old Lady of South King Street (Dublin: Gaiety Theatre, 2007)

• George C. D. Odell, Annals of the New York Stage, vols. 8 and 9 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1936, 1937)

• Old Fulton NY Post Cards website – various mentions of Gunn and Sudlow

• George R. Sims, My Life: Sixty Years’ Recollections of Bohemian London (London: Eveleigh Nash, 1927)

• Emily Soldene, My Theatrical and Musical Recollections (London: Downey & Co. 1897)

• Souvenir of the Twenty-fifth Anniversary of the Opening of the Gaiety Theatre, 27th November 1871, with Michael Gunn’s Compts (Dublin, 1896)

• The Spirit of the Times (New York), 27 December 1873 (‘encored every evening’)

• The Stage, 24 October 1901 (‘Death of Mr. Michael Gunn’)

• Adrian J. M. Stevenson, 13 Westland Row, Dublin website

• Colin Sudlow, posts on Ancestry message boards, February 2012

• Thom’s Almanac and Official Directory for the Year 1862 (Dublin: Alexander Thom, 1862)

• The Times, 9–12 April 1861 (omnibus accident), 10 February and 10 March 1880 (Theatre Royal fire)

• ‘Victorian Burlesque’ at Wikipedia

Fascinating details about these energetic theatre people, after masses of research. I hope their descendants know about the Gunns and are proud of them. I love the Buffalo Bill story!

LikeLike

Boffo! This ought to be a book…..!!!

LikeLike

Another epic piece of research my friend, no wonder we haven’t heard from you in a while. I too liked the Buffalo Bill story but was completely bowled over by the tale of the lock man who drowned a busload of people because he couldn’t tell the difference between a bus and a boat.

LikeLike

This is the story of my great grand father and mother. I have a few mementos of the Gaiety Theatre, including 2 silver ‘potato dishes’ or ‘plate warmers’ celebrating the 25th anniversary of the theatre. Also I still use the beautiful Irish linen sheets and hand towels belonging to Bessie, with her embroidered monogram on them. It was great to come across this piece about them. Their son Selskar was a Professor at MIT, he was also Vice-President of the Rockefeller Foundation for a while. I knew about the drowning, so sad.

LikeLike

Bessie was my great, great grandmother. Bessie’s daughter Haidee (also an actress) gave birth to an illegitmate child in Vienna. That little girl ,Joyce, was my grand-mother. Joyce grew up to be a dancer and married an actor. I’m researching the Gunn family and am keen to learn more.

LikeLike

I believe the daughter of John Gunn Jr (and his wife Hilda nee Killock) was Gladys Hilda Barbara Kate Gunn, aka actress Gladys Henson (1897-1982) who married actor Leslie Henson in 1926.

LikeLike