In an overgrown grave beneath an almost illegible headstone in Islington Cemetery lie the remains of someone who performed before eleven crowned heads of Europe as well as in America, before ending up ‘in very needy circumstances’ as the subject of an appeal for donations for his support.

George Proctor Hutchinson was born in Birmingham on 13 May 1827, the fourth of five children – three boys and two girls – born to Thomas Proctor Hutchinson and his wife, Susanna, née Holloway. The oldest child, James, took up his father’s profession of moulder. But George and his other brother – seven years his senior and also named Thomas – went into show business.

Their debut was with Edwin Hughes’s circus, with whom at the end of March 1847 they arrived in London to take part in performances of The Desert, or the Imaum’s Daughter at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. Queen Victoria attended a matinee on 29 April, with Prince Albert and other members of the royal family. She thought it ‘beautifully put on the stage & got up as to scenery, dresses & grouping. All the horses, elephants & camels of Mr. Hughes’s establishment appeared … An attack by Bedouins was admirably managed, as also the affect of clouds of dust & the desert starlight. The final procession with many horses & a chariot drawn by 2 elephants was very fine.’ The account of the visit in the queen’s surviving journals makes no mention of the brothers; nevertheless, they were to milk having played before her for all it was worth thereafter.

A poster blank for Edwin Hughes’s circus (© Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

In March 1848 they were performing as the Brothers Hutchinson at The Theatre in Carlisle. The Carlisle Journal thought they ‘added in a great degree to the entertainments of the week by the display of their many clever and surprising gymnastic feats’, and a correspondent for the show-business paper The Era thought them ‘truly astonishing and clever artistes’, while commenting that they had done ‘very indifferent’ business thanks to Tournaire’s French Equestrian Troupe having opened ‘a circus which is very well attended’ in competition.

In the following month the brothers had joined Tournaire’s company and they would appear with it in Newcastle, Whitehaven and Carlisle again, en route to Edinburgh.

In March 1849 –now with a company of their own – they gave an ‘astonishing exhibition’ at the Guildhall in Fife. At the end of May they were in Hartlepool, in June in Darlington, July in Hull, and in October 1849 they were at the Queen’s Theatre in Manchester, whether on the same bill as The Blighted Troth or following that ‘domestic drama’ is not clear.

A poster for the Brothers Hutchinson’s appearances in Hartlepool on 31 May and 1 June 1849 (Mike Armstrong / Tyne and Wear Archives)

Then in November they were in Ireland, and the Limerick and Clare Examiner declared that ‘We never witnessed anything of an artistic character that pleased us half so much’ as their ‘Dance of the Globes’ routine at Limerick’s Theatre Royal, where ‘before commencing their part of the entertainment, [they] appeared on the stage in a gorgeous uniform of golden hue.’ The ‘Dance of the Globes’ was probably the routine later called the ‘Sports of Atlas’ and described as follows:

They call it the ‘Sports of Atlas,’ but the globes in this case are borne on the feet and legs instead of the shoulders. The dexterity, agility and muscular power displayed is truly extraordinary, and must be seen to be properly appreciated. The brothers lay on their backs, side by side, and take each a large globe on his feet, which are tossed from one to the other with wonderful rapidity and with numberless variations, all of them very surprising. The last feat is with four globes, which are kept whirling in the air in a manner to completely mystify and bewilder the beholder.

A week after its favourable review, however, the Examiner commented that

Some parties in this city, not friendly to the Dramatis Personæ, have, we understand, propagated a rumour that such performances are not such as Ladies may witness. A more ridiculously absurd notion could not possibly be entertained. There is nothing in those extraordinary feats that the most prudish may not witness with the strictest propriety; were it otherwise they should not have our advocacy, however expert they may be.

The brothers seem to have remained in Limerick for the rest of the year and then toured around Ireland for all of 1850 and 1851, visiting some towns more than once. But in March 1852 they were in Ashton in north-west England, before playing in Manchester in April and May and then moving on to London, opening at the Rosemary Branch Gardens, Islington, in June and staying there for three months.

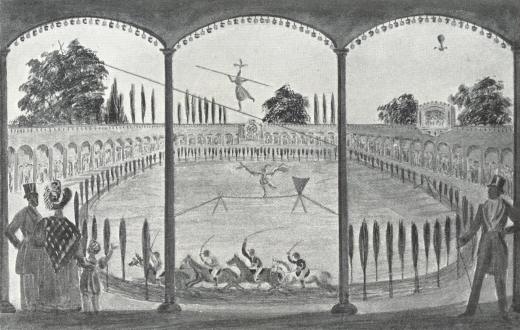

The Rosemary Branch Gardens in 1846 (from Warwick Wroth, Cremorne and the Later London Gardens)

In October they were at the Royal Marylebone Theatre, providing a coda to performances by ‘the celebrated American Tragedian’ McKean Buchanan in King Lear, Hamlet, Othello, Macbeth and Richard III, and themselves followed by Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

The following months found them in Southampton, Ireland and Edinburgh again, then in February 1853 they appeared with Hernandez & Stone’s American Circus in Manchester, presenting ‘many novel feats’. But by the end of March they had moved on, and, with the American Circus then in Bradford, in April 1853 they were appearing opposite The Slave Hunt at the Princess’ Theatre in Leeds.

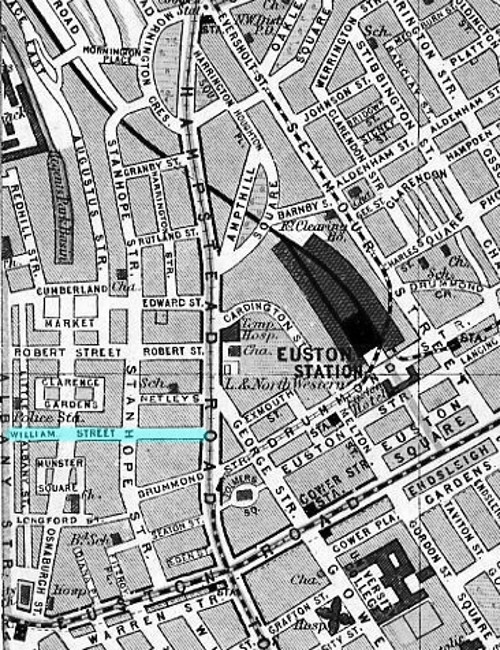

That the British Newspaper Archive contains no mention of them for some time after this may be explained by an advertisement in the Beverley Guardian and East Riding Advertiser of 29 November 1856, which details appearances before ‘the following Crowned Heads of Europe’: the king and royal family of Denmark (Copenhagen, 12 May 1853), Prince Frederick William and the royal family of Prussia (Berlin, 21 August 1853), the king and royal family of Saxony (Dresden, 9 September 1853), the emperor and royal family of Austria (Vienna, 28 November 1853), the king and royal family of Hanover (Hanover, 25 June 1854), the king and crowned prince of Sweden (Stockholm, 19 January 1855) – and Queen Victoria, of course. (An 1857 ad in The Era also mentioned Emperor Napoleon III, the emperor of Russia, the sultan of Turkey and the queen of Spain.) They had also, the ad said, performed ‘before most of the Nobility on the Continent’. At the Victoria Pavilion in Copenhagen, The Era had reported in August 1855, their performances were so popular that ‘many could not get in’, and ‘On the last night 1,200 paid for places in the large marquee. Farmers came so far as thirty-two English miles, and were obliged to return without seeing the entertainment.’ In Vienna, Die Presse praised their ‘sturdy physique and beautiful appearance’ and a skill in gymnastic exercises which ‘captivates the eye through the grace of the movements’. And now– ‘FOR TWO NIGHTS ONLY!’ – the brothers were coming to the Large Assembly Room, Beverley, Yorkshire.

Given the above, it comes as something as a surprise to learn from an advertisement in advance of performances in Portsmouth in April 1856 that ‘The Brothers Hutchinson have just Returned from a four-years’ sojourn in Russia, including the whole period of the present [Crimean] War. Mr. THOMAS P. HUTCHINSON will, during the Evening, exhibit various Trophies, and deliver a 10-minutes’ oration relative to his treatment by the Russians during his travels in their Country.’

After Portsmouth, they then appeared for some months at the Royal Cremorne Gardens in Chelsea, followed by the Royal Pavilion Gardens in Woolwich and the Rosherville Gardens in Gravesend, after which they again headed north, ending 1856 as part of W. Sanger’s Allied Circus in South Shields.

Cremorne Gardens in the Height of the Season, by M’Connell, 1858 (from Warwick Wroth, Cremorne and the Later London Gardens)

Although the South Shields engagement was billed as ‘positively the last SIX NIGHTS of their stay in England’, from January to March 1857 they were performing ‘Les Merveilles Vivantes’ with Macarte’s Cirque Imperial in Birmingham, then were back with Sanger’s again in Newcastle, presenting a ‘DRAWING ROOM ENTERTAINMENT of GYMNASTIC POSIES [sic], as performed before Five Crowned Heads, including her present Majesty’, before in April advertising themselves as ‘disengaged’ until appearances in Bradford from late April to early May with the ‘Equestrian Manager’ Pablo Fanque, né William Darby – the first recorded non-white circus owner in Britain – after which they would be free for twelve days. They were back in Birmingham in May, and ended the month with a return to Rosherville Gardens, where they remained until September with their own ‘Grand Continental Troupe of Artistes’, whose show was included with the price of admission to the gardens.

Rosherville Gardens, Gravesend (Illustrated London News)

In advance of two performances in Maidstone on 23 and 24 September they advertised that

The BROTHERS HUTCHINSON beg respectfully to call the public’s attention to the novel Programme of Entertainments which they have selected for their amusement, at the same time assuring their Patrons that all the Performances announced are of a Classical Nature, and calculated to please the most fastidious. Many long years of laborious toil and study have been spent to accomplish the great Feats which they have the honour of presenting to you, and on which occasion they most respectfully solicit your patronage.

However, on their first night ‘Only twenty-five persons presented themselves for admittance, and to these their money was returned, the performance not taking place.’ So it was then back to Gravesend, followed by a tour of Kent and then on to Southampton, Cork and, from mid-December into January, Liverpool, where they starred in William Cooke’s Circus at the Amphitheatre in Liverpool.

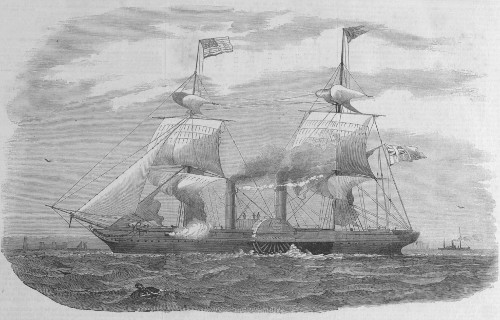

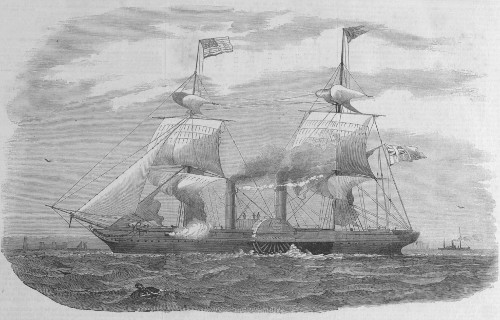

On 23 March 1858 an ad in the New York Herald announced ‘TO THEATRICAL MANAGERS AND THE PUBLIC – Arrival of distinguished gymnasts – The BROTHERS HUTCHINSON, the renowned gymnastic artists, from the Theatre Royal Drury Lane, Astley’s Royal Amphitheatre, London, have arrived by the Arabia … Letters should be addressed to the Brothers Hutchinson, at the Florence Hotel, 400 Broadway.’

Cunard’s steamship Arabia, which carried the Brothers Hutchinson to New York (Illustrated London News)

On 29 March they made their American debut as one of the entr’acte turns in Thomas Dunn English’s The Mormons, or, Life in Salt Lake City at Burton’s New Theatre in New York, presenting their ‘Sports of Atlas’ routine. It was advertised that ‘The BROTHERS HUTCHINSON will go through their wondrous and elegant performances, as given before the Queen of England, the Monarchs of Russia, Austria, Prussia, Sweden and Norway, Saxony and Hanover. The testimonials from these countries, with the signatures of the various kings, may be seen at the Box office.’

On the following day the New York Herald gave the description of the ‘Sports of Atlas’ routine quoted earlier, with a sniffy conclusion that ‘These feats are not a very high order of entertainment, but for people who fancy that kind of thing they are very fine and must prove attractive.’

The Mormons played in New York until 2 May, after which it moved to San Francisco, but the brothers’ association with it didn’t last that long, for on 24 April the Syracuse Daily Courier carried an advertisement for five appearances they were making at ‘Plunkett’s Dramatic Temple (Corinthian Hall)’ in April–May. The ad gives an idea of their act:

PART FIRST

Raphael’s Dream, or Studies from the Ancient Masters. Concluding with the Fighting and Dying Gladiators, in three positions …

After which the exquisite performance of the highly-trained and beautiful CANINE PETS, which were exhibited on two occasions, by special command, before Her Majesty and the Royal Family at Winsor [sic] Castle. These docile and intelligent animals were trained by Mr. Geo. P. Hutchinson, by whom they will be introduced to the patrons of the night.

P.S. – They will on this occasion repeat their Great Ladder Dance.

To be followed by Illustrations of the Arena, or the Roman Wrestlers, embracing every description of Roman attack and defence practiced in the Gladiatorial contests before the Roman Emperors, and thousands of spectators in the Magnificent Collisium [sic], concluding with the tremendous Contest with the Lance! …

Then, the crowning act of these great artistes, the SPORTS OF ATLAS, comprising a variety of evolutions with 1, 2, 3 and 4 Silver Globes, a feat invented and performed solely by the Brothers Hutchinson!

Appearances were advertised with Tournaire and Whitby’s New York National Circus in Brooklyn, Williamsburg, New Jersey City and ‘all the principal towns on the North River’ later in May. When, as part of Hutchinson & Yates’ Celebrated English and American Gymnastic, Acrobatic, Ballet, and Concert Troupe, they appeared at Rand’s Hall in Troy, NY, in June 1858 the Troy Daily Whig found ‘their illustrations of the Roman arena, and delineations of works of art, were wonderful as well as pleasing’, though ‘The house was not as full as it should have been for the high order of performance, and the ability and talent of the members of the troupe.’

The brothers appeared at the Metropolitan Gardens in New York from late June until August, then they seem to disappear from online newspaper archives until in February 1859 ‘These WONDERS OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY’ are billed as appearing in New Orleans. In May that year the New York Clipper announced that they had been performing at the Concert Hall in Columbus, Georgia, and that

On the 16th, they opened a new gymnasium for athletic exercises, at the same hall, as much as to say – ‘There’s my next best – beat it if you can.’ On the 23d, their fencing, sparring and scientific class commenced under the guidance of Prof. Thos. P. Hutchinson, who seems to say – ‘If we don’t give satisfaction, may I be elected to bring in the groceries!’

On 26 June 1859 The Era reported that they were expected to be back in London around mid-July ‘for the purpose of playing a few engagements prior to their final retirement from the profession, and return to the United States’, but it wasn’t until 17 September that the New York Clipper announced that ‘The brothers Hutchinson, gymnasts, have arrived in London after their tour through the United States.’

In June 1860 advertisements for the ‘disengaged’ Madame Delevanti – ‘whose astounding performances as an ascensionist on the TELEGRAPH WIRE and TIGHT ROPE have electrified every audience before whom she has had the honour of appearing’ – emphasised that ‘Mr George Hutchinson, of the renowned Brothers Hutchinson, will accompany Madame Delevanti as Clown and Gymnast, with his Canine troupe,’ and at the end of the month an ad in the Birmingham Journal for the ‘FIRST GRAND FETE OF THE SEASON’ at Aston Park on 16 July stated that the event would include Mme D. and

Mr. George Hutchinson,

Of the renowned Brothers Hutchinson, his unrivalled

GYMNASTIC TOUBILLON STILT ACT,

BACCHANALIAN GAMBOLS,

and Classical Representations of

GRECIAN AND ROMAN STATUARY,

Amidst a magnificent display of Coloured Fires.

In September, Astley’s Royal Amphitheatre advertised the ‘Re-engagement of the celebrated Delevanti Troupe, Mr. George Hutchinson, and the wonder of the world, the Great Little Menoni’. So what had happened to brother Thomas? An ad in The Era on 9 December 1860 explains:

Great BENEFIT Performance. Thos. P. Hutchinson, one of the Brothers Hutchinson, and a native of Birmingham, who has been stricken with that worst of all calamities, Blindness, begs to announce to the inhabitants of his native city, that Mr G. W. Cassidy, the liberal Proprietor of the Royal Grecian Amphitheatre, in Moor-street, has most generously placed his magnificent Circus and British Company at his (T.P.H.’s) disposal for a Grand BENEFIT Performance on WEDNESDAY NEXT … The entertainments will be of the highest order, and the whole of this Great Company will appear.

Thomas would later become a professor of gymnastics in Manchester. He died in Barnet in 1885.

Without his brother, George seems to have adapted their ‘Sports of Atlas’ routine and to have given more prominence to his performing dogs. He was in Gravesend in August 1861 and Portsmouth in September, And in October 1961 The Era reported that at the London Pavilion ‘Mr. G. P. Hutchinson is almost beyond compare in his pleasingly attractive performances with the barrels and globes on his feet and hands. His trained dogs, too, must have been wonderfully tutored to perform the tricks they do.’

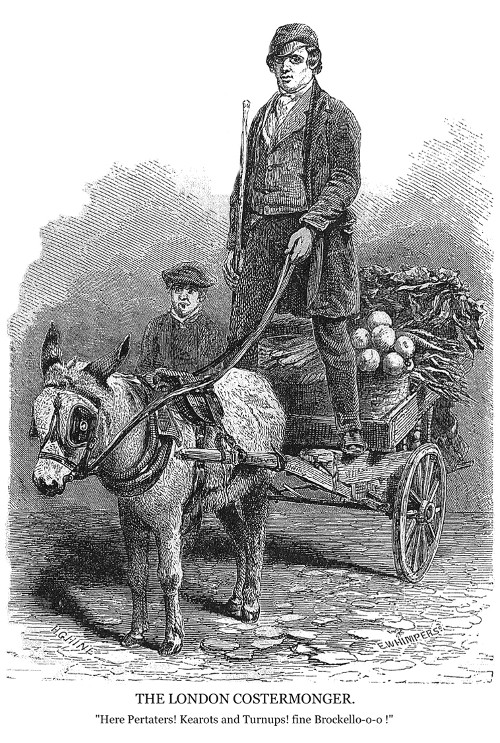

An illustration used in several advertisements for events featuring Hutchinson’s dog troupe. An 1866 ad claimed that ‘A description of the various feats that these sagacious special favorites have been taught to execute would surpass belief, Their intelligence, style and finish exceed every kind of training the brute species ever developed, and the amusing alacrity, and the immense docility displayed in their unique performances, call forth shouts of applause.’

He appeared in various London music halls in early 1862, and on 4 July that year he was on the bill for the Barnsbury Literary Institute’s Midsummer Juvenile Entertainment at Myddleton Hall. The Islington Gazette wrote that

Mr. G. P. Hutchinson and his dogs form a very united trio, and were decidedly the ‘winners’ at the juvenile entertainment. Docile and intelligent these animals certainly proved themselves in an extraordinary degree; their fondness for their master is evident, and their enjoyment of the performances appears in anticipating their master’s commands with an eagerness that showed coercion has nothing to do with their training. Mr. Hutchinson’s leadership cannot be too highly eulogised; he is active, spirited, and stirring.

But the Gazette added a rather baffling qualification to this praise:

There is one flaw, however, which we leave to his good taste to correct, we refer to the exposure of the hoop. Now, much as we dislike the hoop encumbrance, as alike inelegant to woman and incommodious to men, we yet think the exhibition of the skeleton hoop on the person of the dog more offensive than satisfactory. It will take all the skill of a very wise leech to cure this dropsical malady, and until this physician makes plain to the highest circles that they are cherishing a deformity, we, of lower degree, must be content to endure. With this little exception we commend Mr. Hutchinson and his faithful dogs to the attention of a sight-seeing public, who cannot fail to be gratified with these admirable performers.

Hutchinson made a number of performances at the Middlesex New Music Hall, Drury Lane, and at the Oxford, in Oxford Street, in the next eighteen months, and in July 1862 the Raglan Music Hall presented a ‘capital evening’s entertainment’ at a benefit for him. In various editions of The Era in 1863 he was included in the ‘Excelsior List’ of performers advertised as managed by the agents George Webb and Harry Montague.

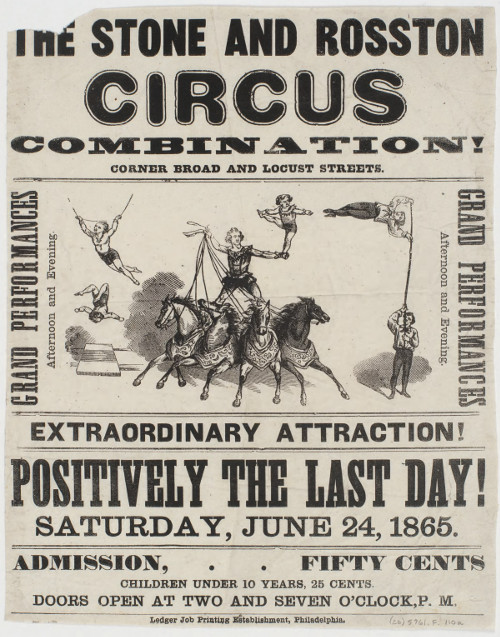

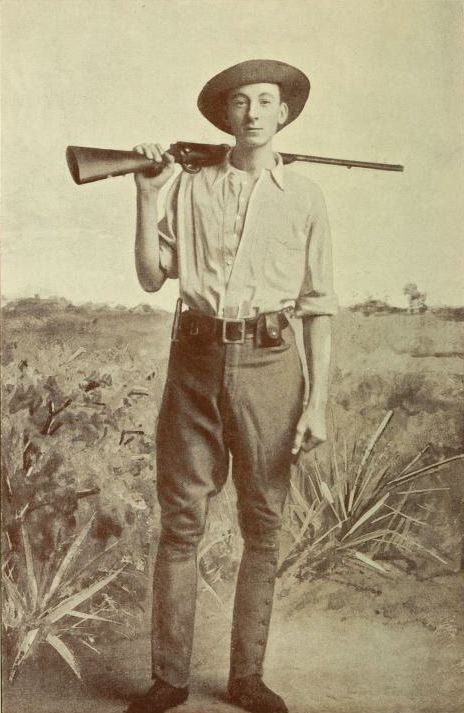

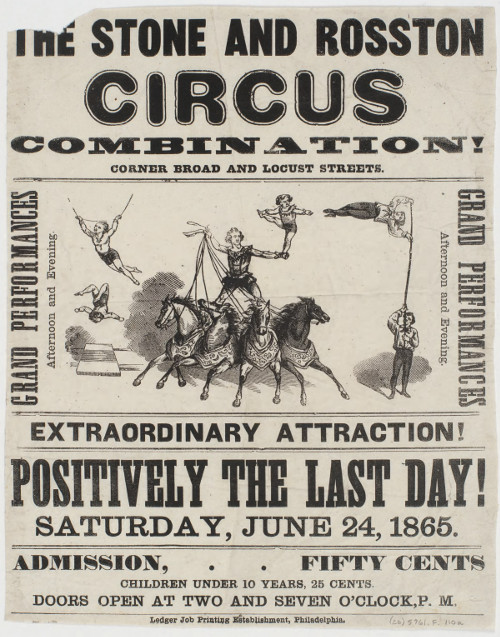

Then in 1864 he returned to the United States. The American acrobat John Hayes Murray had been performing in Europe as part of an act called the Roman Brothers – supposedly reproducing trials of strength performed in ancient Rome – when his partner in the act, George Holland, died suddenly of heart disease. Hutchinson took Holland’s place, and together he and Murray joined Stone & Rosston’s Circus, where they were billed as ‘The Excelsior Gymnasts’ and the like, and where ‘Prof. G. P. Hutchinson’ presented his ‘WONDERFUL DOGS, trained to a point of perfection almost incredible’.

A poster for Stone & Rosston’s Circus (Library Company of Philadelphia)

From May 1864 they performed around the western states – from 1866 as part of Stone, Rosston & Murray’s Grand Combination Southern Circus (with (John H. Murray ‘the Prince of Gymnasts’ and G. P. Hutchinson ‘the Aerobatic and Athletic Anomaly’) and from 1868 as part of Stone & Murray’s Combination Circus. In March 1867, while the Stone, Rosston & Murray troupe was in winter quarters, Hutchinson also presented his dogs at the New York Circus.

In March 1870 the New York Clipper commented that Stone & Murray’s Circus ‘enjoys a reputation second to none in the country’, and reported that ‘George P. Hutchinson lately left for Europe in search of novelties, and it is thought will return in time to commence the season with the party.’ But he did not return, and in September 1870 an ad in The Era announced that Hutchinson would be making ‘his only appearance after ten years’ [sic] absence in America’ at the Crystal Palace Concert Hall in Birmingham. Then in April 1871 he re-emerged as one of the proprietors of Bell & Hutchinson’s Great United States Circus, which was beginning its ‘First Tour through England’, boasting that

All the Artistes engaged are new to the British Public.

The Carriages and Paraphernalia all New!

One Hundred Horses!

The Finest Trained Horses in the World!

Fifty Performers!

One Hundred and Fifty Supernumerraies [sic]! The Best Band Travelling!

Venues visited included Gloucester, Chepstow, Shrewsbury, Grantham, Gravesend, Canterbury and Hastings. In September a correspondent from Vienna’s Neue Freie Presse saw it in a ‘small English town’ and was not impressed:

Several days in advance of the company’s arrival in a tiny corner of the country, posters elegantly printed in green and red present the artistic programme … In order to tie in with current events, representations of the battle of Wörth and the capture of Sedan are promised as key attractions. ‘In the interests of the esteemed public,’ it is stated, ‘the proprietors of the circus have turned their undivided attention to the course of the Franco-Prussian war … At great cost they have bought up large quantities of munitions from both sides and with these will present the scenes from Wörth and Sedan … ’

The troupe moves into town. All the inhabitants lean inquisitively out of their windows and swarm on to the streets … First to appear is a triumphal carriage, fantastically decorated in gold and drawn by four horses, followed by the ‘munitions’. These consist of a black-painted wooden cannon and a model of Fort Mont-Valérien made of wood and cardboard; only Messrs Bell and Hutchinson will know what this has to do with Wörth and Sedan. After this the heroes of the war ride past us: a youthful version of King Wilhelm; Napoleon, whose identity can barely be ascertained from his mask; a few Prussian uhlans and French lancers. Voila tout!

The performance begins; three clowns and three head grooms play the main roles by filling out the greater part of the evening with cheap jokes; a few gymnasts and trick riders with a number of horses – a total of 30 at most, instead of the advertised 150 – have to do the rest. In the battle tableau, the one cannon has to provide the final effect by means of red Bengal light … One thing is certain: no one is startled by gunshots, because that would require gunpowder, and gunpowder is expensive.

Later in September a notice in The Era advertised the availability of the circus’s performers from the end of October, but in the following February the company was on the road again, travelling across the south and west. In April 1872 an ad in the Aldershot Military Gazette promised a ‘grand procession’ including

THE GRAND TABLEAU CHARIOT

Representing the Sultan of Turkey surrounded by his Ladies of the Harem and their attendants, in full Turkish Costume. This Magnificent Chariot cost £1,000, and will be drawn by Nine Powerful Horses, in State Harness.

Readers of the Thanet Advertiser were assured that ‘THE CLOWNS will be found witty without being vulgar.’

In July the circus was ‘now Travelling on the Continent’, and in August the Edinburgh Evening News reported that

An exciting scene took place at Ham, in Belgium, in consequence of the escape early in the morning of four of the five lions belonging to Messrs Bell & Hutchinson’s American Circus … At 10 a.m. the lions were all secured and brought back to their cage, after a most exciting chase of five hours, for which the greatest credit is due to the tamer, the attendants, the gendarmes, and the peasantry co-operating.

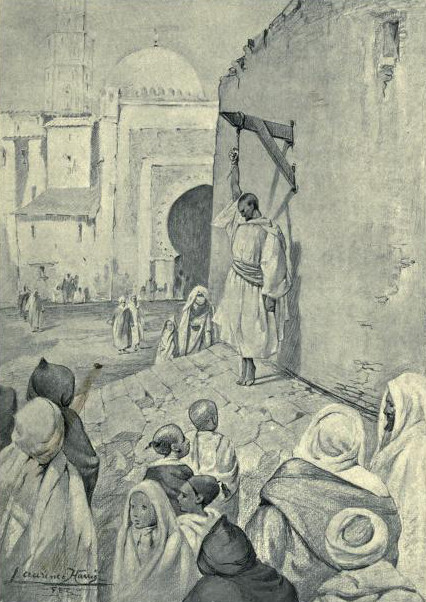

In September 1974 the Paris Journal amusant noted that ‘The Circus of MM. Bell and Hutchison is accompanied by twenty famous Egyptian Eunuchs, who have been specially raised for the relaxation of the Ladies of the Harem of the Viceroy of Egypt, and who show themselves in Europe for the first time.’

The circus remained on the Continent until late 1874, when mentions of it in The Era come to an end.

It may have been soon after this that Hutchinson started working for the American circus proprietor James Washington Myers. Born in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1823, Myers had begun his circus career aged 9, as a bareback rider and acrobat. In 1857 he came to England as a member of the Howes & Cushing Circus, which in 1858 had a triumphant run at the Alhambra Palace in Leicester Square and performed for Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle. When Howes and Cushing returned to the USA in 1864, Myers did not go with them but formed his own company, J. W. Myers’s Great American Circus, with which he continued to tour Great Britain and eventually Europe. He even visited Egypt in 1868. Then in 1875 he put up a permanent circus structure at the Place du Château d’Eau (now the Place de la République) in Paris, where Hutchinson became his manager. From January 1879 Myers relocated to the Agricultural Hall in Islington for three months, after which his company toured the country.

An 1876 poster for J. W. Myers’s Great American Circus at the Place du Château d’Eau (gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France)

Hutchinson left Myers at some point, and from July 1880 till November 1887, The Era later reported, he served as treasurer for the John Holden company of marionettes, which was mainly based in Europe from the late 1870s to the mid 1880s – in 1884 Le Courrier du Pas du Calais reported that the company’s show could fill an entire train.

John Holden’s letterhead (gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France)

After leaving Holden, Hutchinson was employed irregularly on the staff of the Agricultural Hall; then on 5 March 1898 a letter in The Era announced a testimonial benefit for him, as, ‘now in his seventy-first year, and through no fault of his own’, he was ‘in very needy circumstances’. It quoted the circus proprietor ‘Lord’ George Sanger as saying that ‘to my knowledge a more respectable man, both in youth and age, does not live at the present day … I have no doubt the awful affliction to his brother – his insanity and blindness – has been the cause of [his] present distressed condition.’ But three weeks later an article in the same paper reported that, on 22 March, Hutchinson had ‘succumbed … to a complication of disorders’. He was buried in Islington Cemetery on the 25th.

Hutchinson’s grave in Islington Cemetery

SOURCES

• Aldershot Military Gazette, 11 May 1872 (‘grand procession’)

• The Atlas, 1 September 1860 (‘Re-engagement of the celebrated Delevanti Troupe’)

• Beverley Guardian and East Riding Advertiser, 29 November 1856 (‘Crowned Heads of Europe’)

• Birmingham Journal, 30 June 1860 (‘FIRST GRAND FETE OF THE SEASON’)

• British Newspaper Archive – various mentions of Hutchinson

• Carlisle Journal, 17 March 1848 (‘many clever and surprising gymnastic feats’)

• Chronicling America website – various mentions of Hutchinson

• Daily Courier (Syracuse, NY), 24 April 1858 (‘Plunkett’s Dramatic Temple’)

• Daily Whig (Troy, NY), 2 June 1858 (‘illustrations of the Roman arena’)

• Edinburgh Evening News, 16 August 1873 (‘An exciting scene’)

• The Era, 26 March 1848 (‘truly astonishing and clever artistes’), 7 October 1849 (The Blighted Troth), 27 February 1853 (‘many novel feats’), 26 August 1855 (‘many could not get in’), 12 April 1957 (with ‘Equestrian Manager’ Pablo Fanque), 8 November 1857 (distinguished patronage), 26 June 1859 (’final retirement from the profession’), 10 June 1860 (’will accompany Madame Delavanti’), 9 December 1860 (’Great BENEFIT Performance’), 27 October 1861 (’almost beyond compare’), 20 July 1862 (‘capital evening’s entertainment’), 25 October 1867 (‘at liberty’), 25 September 1870 (‘ten years’ absence in America’), 7 July 1872 (‘now Travelling on the Continent’), 5 March 1898 (‘in very needy circumstances’), 26 March 1898 (death announced)

• Evening Star (Washington, DC), 30 March 1865 (‘Excelsior Gymnasts’, ‘WONDERFUL DOGS’)

• Fife Herald, 22 March 1849 (‘astonishing exhibition’)

• Illinois Digital Newspaper Collections – various mentions of Hutchinson

• Illustrated London News, 1 October 1842 (Rosherville Gardens), 8 January 1853 (Arabia)

• Islington Gazette, 12 July 1862 (‘a very united trio’)

• ‘James Washington Myers’ at Circopedia

• Megan Sanborn Jones, Performing American Identity in Anti-Mormon Melodrama (Routledge: Abingdon and New York, 2009)

• Le Journal amusant, 26 September 1874 (‘famous Egyptian Eunuchs’)

• Limerick and Clare Examiner, 21 November 1849 (‘a gorgeous uniform of golden hue’), 28 November 1849 (‘strictest propriety’)

• John McCormick, The Holdens: Monarchs of the Marionette Theatre (London: Society for Theatre Research, 2018)

• Maidstone Journal and Kentish Advertiser, 19 September 1957 (‘Grand Continental Troupe of Artistes’), 22 September 1857 (‘novel Programme of Entertainments’), 26 September 1857 (‘very different reception’)

• Memphis Appeal, 26 January 1866 (‘sagacious special favorites’)

• New Orleans Daily Crescent, 3 February 1859 (‘WONDERS OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY’)

• New York Clipper, 28 May 1859 (‘opened a new gymnasium’), 17 September 1859 (‘arrived in London’), 26 March 1870 (‘lately left for Europe’)

• New York Herald, 23 March 1858 (’Arrival of distinguished gymnasts’), 29 March 1858 (’wondrous and elegant performances’), 30 March 1858 (‘not a very high order of entertainment’)

• Newcastle Courant, 13 March 1857 (‘GYMNASTIC POSIES’)

• Neue Freie Presse (Vienna), 14 September 1871 (‘Zur Naturgeschichte der Reclame’ – with thanks to Arthur Fleiss for his help with this)

• North & South Shields Gazette and Northumberland and Durham Advertiser, 4 December 1856 (‘positively the last SIX NIGHTS’)

• George C. D. Odell, Annals of the New York Stage, vol. 7 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1931)

• ‘Pablo Fanque’, at Wikipedia

• Portland Daily Press (Maine), 29 May 1867 (‘Aerobatic and Athletic Anomaly’)

• Portsmouth Times and Naval Gazette, 29 March 1856 (‘a four-years’ sojourn in Russia’)

• Die Presse (Vienna), 24 November 1853 (‘sturdy physique and beautiful forms’)

• Queen Victoria’s Journals, 29 April 1847

• Reynolds Newspaper, 10 October 1852 (‘celebrated American Tragedian’)

• Shepton Mallet Journal, 1 September 1871 (‘First Tour through England’)

• William L. Slout, Olympians of the Sawdust Circle: A Biographical Dictionary of the Nineteenth Century American Circus

• John Stewart, The Acrobat: Arthur Barnes and the Victorian Circus (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2012)

• Thanet Advertiser, 1 June 1872 (‘witty without being vulgar’)

• Warwick Wroth, Cremorne and the Later London Gardens (London: Elliot Stock, 1907)